-The Sons of Camus- Writers International Journal

A Review by Morelle Smith

Issue 13 – Autumn 2017 –

Issue 13 – Autumn 2017 –

An SCW Books Publication –

Review by Morelle Smith

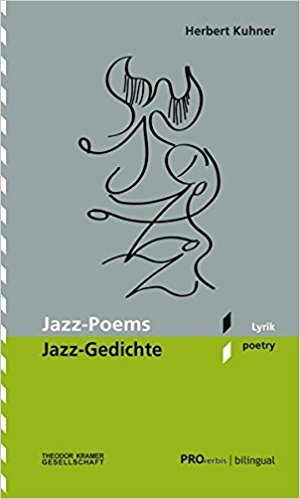

Jazz-Poems: author Herbert Kuhner

Publisher: Proverbis (Andreas Schinko), Vienna, Austria (2015\

ISBN: 978-3 -902838-20-9

80 pages

Paperback.

12 Euros

This bi-lingual German/English collection is a series of poems

about jazz and the musicians who played it. Herbert Kuhner says in the introduction that he means them as a tribute to those „bandleaders, sidemen and singers who have enriched my life,“ He then describes some of the obstacles they had to overcome as touring musicians – the stresses of being on the road, the long travelling, the cheap hotels, the smoke-tilled clubs and, for the black musicians, the prejudice. Kuhner says, „They left us a great legacy.“ and it often seems in life that great art comes about despite the very real challenges to its accomplishment; and yet I want to say that art, and the life-course however fraught and difficult, of the artists, are twined around each other in some inextricable design.

Just to select a few of these poems:

„Miles Saw Stars“ describes the racism and police brutality that Miles Davis experienced, (which feels eerily relevant today). „A Rainv Day. in Vienna“ made me laugh. I have toured with musicians and this just the kind of delightful story they tell about other musicians as they sit around after the gig. This one tells of Django Reinhardt who came to the USA to tour and thought the American company would give him a guitar to play – „but they couldn’t even pronounce his name/much less spell it.“

„He Couldn’t Let it be“ and Weill’s „September“ are fascinating stories and are historical and social documents. The former is the extraordinary story of Eddie Rosner, his escape from Nazi Germany, capture in Poland, imprisonment in Siberia where „He formed a gulag band“ and eventually returned to Berlin and music performance. In the latter, we learn that Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht escaped by boat from Germany to the USA „but not the same boat.“ When I first heard, as a child, a recording of Louis Armstrong playing Mack the Knife, I knew nothing of its historical and artistic provenance. This feeds the interest of someone as fascinated as I am by the life stories of artists in theinter-war years in Europe, the stories of flight and (sometimes) freedom, the desperate sense of exile, and equally dangerous fate of those who remained. In many ways this time celebrated the human spirit the ability to endure, and to create, and their stories give inspiration.

And if you did not know beforehand the lyrics Anderson put to Kurt ‚Weill’s music in September Song, you will be introduced to them. And in this wonderful internet age, you can find the song and listen to it, as I did. (I would recommend Ella Fitzgerald’s version).

At this point, I began to recognize Kuhner’s achievement – how do you make a tribute in words to such heartfelt music? Parng down the words in the way he does brings us close to the individual notes, and creates a landscape of its own, sometimes lyrical, but more often rocky, vegetation-bare, letting the vast views out over plains or oceans, speak for themselves. Several of these poems end with positive and uplifting lines that ring and remain in the mind – and perhaps this is an echo too of jazz songs.

Weill’s September ends with a quote from Maxwell Anderson:

„and Kurt managed to make

thousands of beautiful things

during the short and troubled time

he had…“

The last lines of „The New Masses and Café Society are:

„The sponsor insisted that blacks be allowed to listen to blacks, and they got their way. For the first time blacks sat with whites in Carnegie Hall.“

And I particularly like the ending of „The Wild Man“:

„That sassy, sound breaking through

all the sissy music

is the gritty tenor

of the great Arnett Cobb.“

They do not all end that way.‘.Kuhner is a realist and recognizes That the Eternal Coachman‘ is always going to catch up with us, and sometimes much sooner than we anticipate.

At first, it t.as the simplicity of the language that struck me, its conversational, flowing style. I read on with increasing interest in the stories and lives of the people Kuhner writes about and with increasing admiration of the almost invisible technique he uses in these poems, to evoke such a seemingly simple ease and flow. He portrays the musicians and their lives in a series of brush strokes that make me think of Chinese paintings, a few skillful lines creating whole landscape. You do not have to know anything about jazz music to enjoy these landscapes and lives, And you might just discover, as I did, a new depth and poignancy to their music.

Reviewed by Morelle Smith

Users Today : 21

Users Today : 21 Users Yesterday : 87

Users Yesterday : 87 This Month : 622

This Month : 622 This Year : 622

This Year : 622 Total Users : 221758

Total Users : 221758 Views Today : 29

Views Today : 29 Total views : 1955081

Total views : 1955081 Who's Online : 1

Who's Online : 1